bandwidth

content note: developmental trauma disorder, voices, sex, gender, idk idk

This is a follow-up to "attention economy." Really, I should've included these ruminations the first time around. I'm still not sure I'm able to discuss this topic effectively. But it's something I think about a lot: my brain kind of wheels itself in circles trying to grab onto a conclusion.

Always on my mind is the work of Dr Stephen Porges, whose career has been committed to studying neurodivergence, and particularly developmental trauma (ADHD, autism, C/PTSD). He is very well known in the psychology field for his polyvagal theory.

Dr Porges's youngest son has reached out to me a few times over the years to explain the latest updates to his dad’s research, which he feels would benefit me specifically. At some point Dr Porges discovered that people with trauma, including DTD, consistently experience hearing damage or loss. What is damaged is the ability to hear a particular bandwidth of sound that contains the tones and frequencies of human speech. I have subsequently wondered if this might be the reason my ears zero in and focus on various hisses and spit-crackles (i.e. "misophonia"). Sibilance. Ssssibilance.

Because of this acquired hearing damage, Dr Porges posits, people with DTD feel unsafe when hearing the voices of others. So Dr Porges created the Safe and Sound Protocol, which uses audio recordings to retrain the ear to hear these particular frequencies again, and to therefore feel "safe" around them.

But I also catch myself wondering if these particular tones and frequencies I evidently can't hear well—the frequencies of human speech—aren't the ones associated with the voices of cis men?

I sometimes think about the way men will think of a cis woman's voice as 'screechy' even when she isn't, the way cis men might inexplicably hear only criticism and threats in speech that is utterly neutral, the way cis women are socialized to use a 'customer service voice' for their own safety, speaking an octave higher than is authentic or comfortable.

In fact, a quick Internet search will confirm that "men"—blanket generalization here—do process "women's voices" differently. And it also requires more brainpower and effort to process them, the research claims, because cis women's voices contain more waveforms. OK.

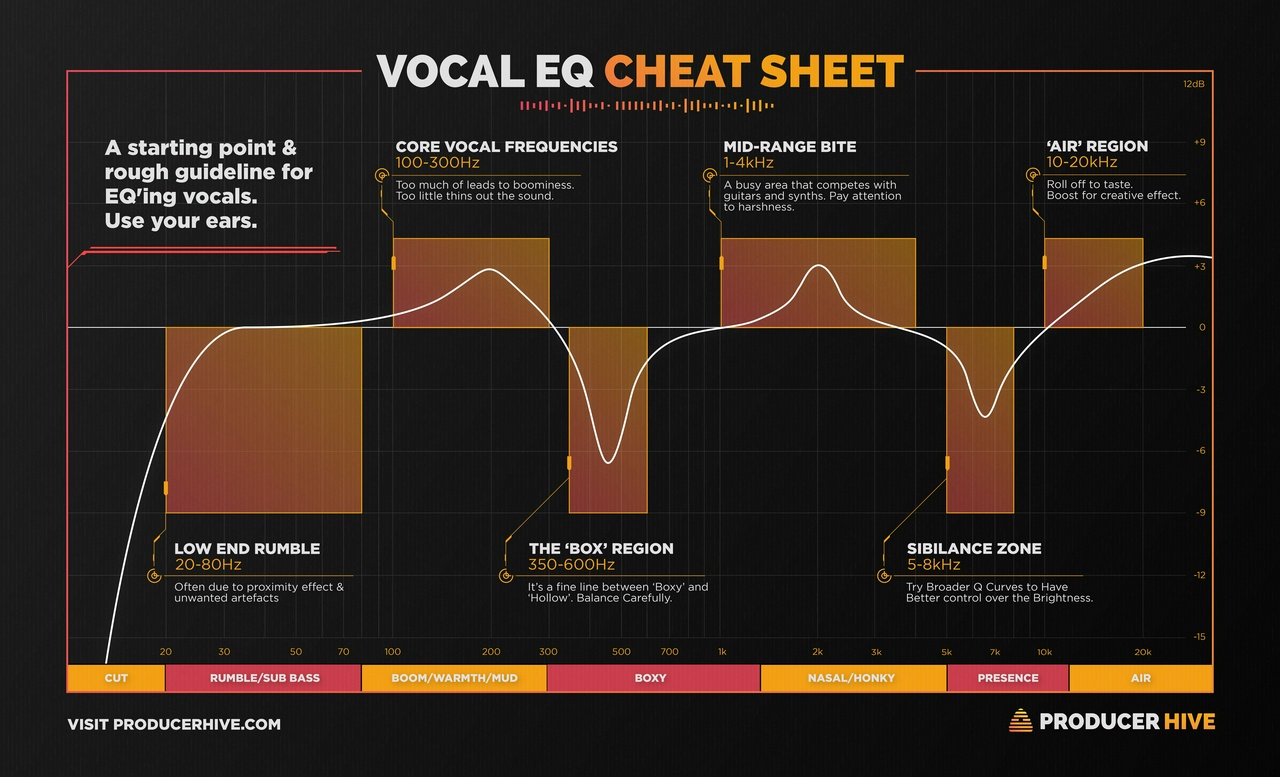

At the final XOXOfest, which was 14 months ago, I'd signed up for karaoke. Singers would go up on a big stage in the outdoor tent. I was nervous. I was worried about my song choice. I kept glancing over at the married couple who were running karaoke from a little folding table. Finally, I turned and explained the source of my anxiety to my friend's husband: By default, the equalizer would be set to pick up cis men's voices. It always is. I have a very low, rich voice, but the equalizer would be unlikely to pick it up. For whatever reason, the frequencies in my voice are just... "outside the curve." If you've ever looked at audio software, the equalizer makes a little graph. Equalizers are usually oversimple, set to pick up the lower range of the left side, then the upper range of the right side.

Okay, I don't even have the language for what I'm trying to describe. But it means my voice will be electronically transmitted as thin and tinny, no matter the register in which I speak or sing—unless I were to mess with the soundboard myself, making my own voice the 'default', I guess.

Anyway, I went up there and sang "Maps." The crowd cheered. I shakily descended the stairs and stood in place in the crowd again. My friend's husband looked like he'd seen a ghost. Then he started laughing. "You were right!" he said to me, astonished. "No one could hear you during the verse. We could only hear you during the chorus. It didn't pick up your voice in the lower register at all." I sighed.

Five months ago, I went to a reception for the release of an audiobook, which had been narrated by the author. The attendees were treated to a recording of the first chapter. My friend's mom was delighted, overwhelmed even, by the richness of the author's voice. I agreed, saying that the sound engineer had done a very professional job of boosting all those dulcet tones in his voice, giving the audio a lot of depth. "A really pro job," I said a few times.

His voice communicated safety, authority. I have noticed that even cats—especially cats!—prefer a voice that is low, that rumbles in the chest. They like to sit on it. Perhaps it feels to them like a mother's reassuring purr.

All my life, people have let me know how much they hate my voice. "Your voice just carries," teachers would tell me. (Carries what?) "You sound just like my older brother," a kid on an elementary-school playground in Seattle would announce. A classmate's mom, chaperoning a school field trip, would stuff fries into my mouth to shut me up while other children laughed. "A cat gargling razor blades," someone wrote, reviewing my voice on Apple Podcasts. Another person—or maybe the same person?—lamented that my voice was overly melodic and sing-songy. One time, much more recently, two men and I were accosted by a stranger, who visibly became agitated by my voice as I attempted to calm him down, who made fun of my voice's shrillness and stupidity before actually escalating physically. ("The voice is for your comfort!" I would shout angrily—later in the night, at absolutely nobody.)

I didn't always have a sing-songy voice; as a little kid I had what is called a "flat affect." But then, when I was 8 years old, I got into theater, and one day I abruptly realized that I did not sound anything like my own imitations of other people. So I worked hard to communicate more clearly by adjusting my pitch and tone, by emphasizing important words, by allowing punctuation to be 'heard' in my voice. (I really enjoy transcribing interviews because I like interpreting where the punctuation should go: it is a type of musical notation.)

At my friend's prodding, I did eventually try the Safe and Sound Protocol, and I might try again soon. Reversing hearing damage can only be a good thing, right? And I don't want to be reactive, perceiving threat where none exists, obviously. But…

What follows isn’t intended to disparage SSP or to diminish the profound amount of research and evidence that has gone into its development. But I started thinking about this particular era in which we are living, and I began to wonder if it weren't perfectly all right that my ears don't want to pick up on a rich, silky, sonorous low purr. What if it's a terrific thing that I cannot hear those frequencies as clearly, cannot force myself to effortlessly feel safe around them? What if my hearing damage and auditory hypervigilance are things that do not need to be corrected? What if neurotypical, heterosexual cis men should be working harder on hearing other people clearly instead?