we love 4

My favorite piece of creative nonfiction is "The Pain Scale" by Eula Biss. It is about, among other things, the challenge of measuring and quantifying physical pain.

However, when the triage nurse asked me to score my current pain on scale of 1 to 10, I was, for the first time in my life, confident. "It's a 9," I told her.

I would go on to explain my scoring rubric to my best friend: "This definitely hurts worse than both ruptured ovarian cysts," I explained. I described a few other examples of excruciating pain. "It hurts slightly less than the day my leg turned purple. That was a 10," I concluded.

After two blown veins, I rejected any further attempts to administer pain medication. Hours passed. I rolled onto my side and moaned. The doctor eventually visited. I could be admitted then and there, she said, or I could return for surgery later. I asked her for the surgeon's opinion. The doctor left to phone. She returned. The surgeon thought, with conservative at-home pain management, it could wait.

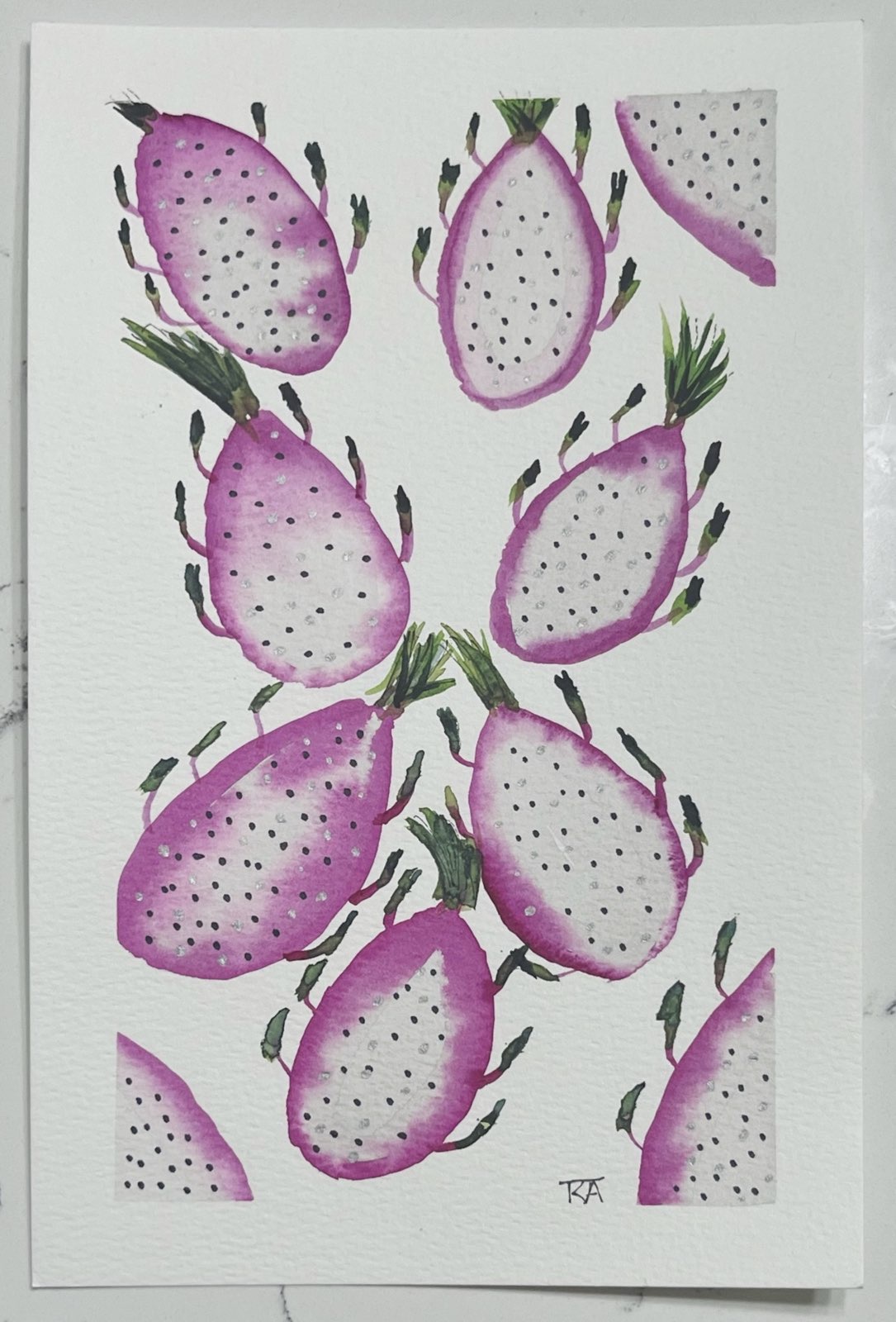

The next morning, I limped up to the pharmacy counter to pick up oxycodone, oral lidocaine, zofran. I remarked on the watercolor paintings of dragonfruit, taped up here and there. The young pharmacist happily explained that her coworker liked to display her paintings at work, and that I could have one if I wanted. The coworker had recently completed a series of summery citrus fruits as well.

I sheepishly pointed at the best painting. "Okay, I'd like that one," I said. "I like the blending." The pharmacist pulled out her phone, and I posed for a photo with my painting of dragonfruit.

"She's gonna love this!" the pharmacist told me of her coworker.

I rationed the opiates and used them sparingly—a good instinct, since the surgical consult was still days away. I apologized to my best friend's 5-year old that we hadn't yet gotten to do all the activities we'd been wanting to accomplish. "It's okay," she said graciously. I thanked her for her understanding—although, later, I wished I'd told her it's still okay to feel disappointed.

My surgeon was an easy, convivial man. "Remind me how to pronounce his last name?" I asked the nurse.

"He won't let you," the nurse replied. "He'll make you call him Rob."

After a lengthy explanation of how ultrasonography works, Rob clicked through images of my gallbladder. There was one enormous stone at the outlet—"like the boulder at the entrance of Jesus' tomb," I told my best friend's brother later. (He laughed. He is a theologian.)

"Wow," I said to Rob, "I wonder what might be hiding in the long shadow it casts," and I nodded at the long V of shadow behind the gallstone, where the image went dark. At another point, when Rob was explaining that laparoscopy depends on luminescent green dye, I commented that a really decent blockage might render the dye useless.

"I'm an anxious patient," I said to Rob then.

"Good," he said. "I think that just means you're grounded in reality. Things happen all the time." We shook hands. The nurse returned with a sheath of instructions and a bag with two bath mitts and a bottle of frothy hibiclens.

On the morning of the surgery, I signed a lot of paperwork in case things happened. I met with the anesthesiologist and with Rob. Then I watched the green dye disappear into my left hand. "It is so green!" I exclaimed. "It looks like what they use to dye the Chicago River on St Patrick's Day."

"We'll only release you when the pain level is a 4," the nurse said. "We aren't looking for zero."

"Oh, we love 4," I said. "Four is a gift." I didn't remember falling asleep, didn't realize I'd already been to surgery and had emerged again. I tried to sit up, and that's how I found out that we were not yet at a 4.

While I was knocked out, Rob had talked to my best friend in the waiting room. He was excited; it was his most challenging surgery in years. It had gone long because the green dye didn't light up shit. Behind the big gallstone had been 13 more gallstones. "There were at least 10 audible fucks," Rob told her. A woman sitting nearby turned and gasped.

Dr. Rob told my friend that I really ought to have been writhing screaming on the ground. He wondered how long this had been going on, how long I'd been living like this? Then he asked if I'd had "a lot of difficult life experiences" because it has been his observation that "those patients" "internalize everything" and "just live with the pain." This astonished my friend.

She brought it up a few times. "How did he know to ask that?" she marveled.

I thought about Dr. Rob's assessment again as I popped some Tylenol. Finally I sat down and messaged a good friend whose surgery had been scheduled for the day before mine. I've never accepted or taken pain medication before now, I wrote. I didn't want to come off as drug-seeking. She'd never thought about it, she replied, but she'd finally accepted a prescription for pain medication late last year—a sort of turning point.

I thought about Eula Biss's essay. I wondered what level of pain other people consider to be normal, tolerable, acceptable. What is the acceptable level of pain to tolerate?

"I mean ideally 'none'," my spouse suggested.

"This isn't the answer either; that's seeking oblivion," I texted back.

"Feeling too much isn't a bad thing," I texted later, unrelatedly. "We are striving for a 4 on the pain scale.

"You would've loved DBT and the 'distress tolerance' module," I continued. "It allows that there is a 'too much' pain level where people stop being rational, and then challenges you to live in a 4, in brackish water."

My spouse reacted to that text with a heart emoji. Brackish water was an analogy we'd discussed early in our relationship. In the Xanth book Demons Don't Dream, a freshwater mermaid and a saltwater merman (or whatever) believe their love is ill-fated—until they realize they can both live together in "brackish water," which is to say, in equal discomfort. Very early in our fledgling relationship I'd evangelized this idea of striving for equal discomfort. I think a surprising amount of relational competition is toward maintaining one's own perfect comfort—which I'll allow isn't totally conscious, since people are "hyper pain-averse," I texted my spouse.

It's why any critique or conflict feels like someone 'trying to do abuse' or 'trying to do harm or pain', when really the average anesthetized person is struggling to constantly coexist in a nice uneasy 4 with others.

Unfortunately, in a marriage, one person having a pain level of 0 might mean the other person is trapped at a 9.

My spouse reacted with a black heart emoji on that one.

I immediately apologized. I know it wasn't really a 0; other circumstances and influences ensured both people were at a 9. Prayer-hands react emoji.